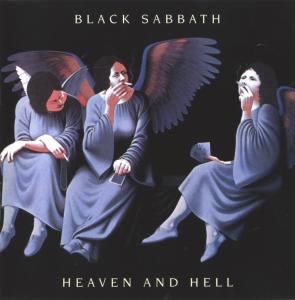

I first heard Black Sabbath at a friend’s house, sometime in 1978. I was 14 years old. That same year, I saw them get utterly destroyed by a young and hungry Van Halen, who opened for them on Sabbath’s ‘Never Say Die’ Tour. Behind the scenes, Ozzy had previously quit the Sabs, but was coaxed back to celebrate the band’s 10th Anniversary with one final album & tour. But somebody must have said ‘Die’, as for all intents and purposes, Black Sabbath as we knew them were over, seemingly the very moment I discovered them.

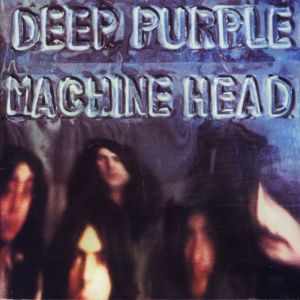

Although I started buying Sabbath records with 1980’s ‘Heaven and Hell’, I back-filled all of the Ozzy-era albums over the next few years. By the time I started collecting records, all of the Ozzy-era Black Sabbath albums were into their umpteenth pressings, and so I unfortunately missed out on some neat features found only in the initial production runs: UK copies of ‘Black Sabbath’ originally shipped in a gatefold sleeve with a creepy poem lurking inside; ‘Master of Reality’ originally came in an embossed cover and included a full-color poster; the early run of ‘Volume IV’ was not only produced as a gatefold, but also had several pages of color pics bound within, like a book. By the early 1980s, none of these features were still in production.

Since I completed my Ozzy Sabbath collection in the pre-internet age, I had no idea that any of these earlier variants existed, until I found a gatefold copy of the debut at a flea market at the local mall. But the most mind-blowing revelation was finding a dilapidated copy of ‘Master of Reality’ at a used record store in Boston in the late 80s. The copy was sans poster, but the vinyl within sported the old khaki green Warner’s label. Cool. I examined those labels closely. What the—

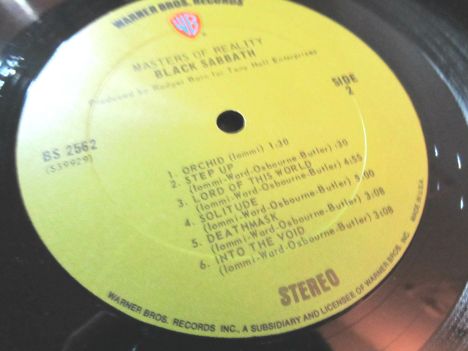

On those labels were titles of songs I had never seen before… ‘The Elegy’… ‘The Haunting’… ‘Step Up’… ‘Deathmask’…?? The room spun around me. Was this some kind of bootleg? Nope, the Warner’s logo was front & center. Did the original version of Master of Reality contain extra songs that had for some reason been removed from subsequent pressings?? Then, like a 5-pound sledgehammer: WERE THERE OZZY-ERA SABBATH SONGS THAT I HAD NEVER HEARD BEFORE???

Well… kinda. Actually, no.

Follow me, if you will, as we ascend downward and backward, into the murky darkness of Black Sabbath’s early years, where we’ll attempt to unravel one of the greatest mysteries of their classic Ozzy-era catalog… We’ll explore musty and worn album covers, moldy old books and faded record labels for the keys to unlock the keys to the Sabbath Code… We’ll travel to that to that cursed and unholy place where Art meets Commerce in an eternal battle for our musical souls. Because it’s true what they say: the Devil is in the details.

Nerd Alert!

On their landmark 1970 debut, Black Sabbath put their live set down on tape as-is, almost completely live, including Iommi’s guitar solo showpiece. Parsing these recordings for a proper track listing was likely a bit problematic in such a free-flowing, jam-like presentation, particularly during the final third of the album. When the original European ‘Black Sabbath’ was released in Europe in February 1970, this arrangement was listed as just two songs: ‘Sleeping Village’ and ‘Warning’, with an extensive untitled guitar solo section occurring inside of ‘The Warning’; four months later, when the album was released in the US, the solo section was given a title: ‘A Bit of Finger’, and all three ‘songs’ were grouped together into one single 14-minute track.

If this was an attempt to clarify this convoluted cluster of music, it failed, because while ‘Finger’ is listed first, the album’s 14-minute climax actually begins with ‘Sleeping Village’. With the last guitar note from ‘Village’ still ringing, ‘Warning’ begins with bass and drums, with no clean break between the songs. Then at around the 7-minute mark, ‘Warning’ transitions into ‘A Bit of Finger’, Iommi’s 6-minute lead guitar showcase, after which the rhythm section re-enters at around 13:00, providing a brief musical bridge for the band to reprise ‘Warning’ and give it a proper ending. Exactly why ‘Finger’ appears first in the track list is a mystery. So, if not to clarify, why alter the track listing at all?

Side One features the same phenomenon: The UK version lists ‘Behind the Wall of Sleep’ and ‘N.I.B.’ as two songs; the US version listed this music as four separate works combined into one track, adding something called ‘The Wasp’, and also gave Geezer Butler’s solo intro to ‘N.I.B.’ a clever title: ‘Bassically’. These changes to how this music was identified resulted in two songs becoming four. Again: Why were intros, and other sections of songs broken out and given their own titles for the US market, identifying them as distinct pieces of music?

Simple answer: Money. The Warner’s deal for the US afforded band an opportunity to negotiate a new publishing deal, and more songs = more publishing money, for both band and publisher. Bill Ward has himself once responded to an interview question regarding these titles by stating that the band needed a minimum of 10 songs per album to satisfy the requirements of their publishing agreement; Ward was likely referring to their US publishing deal, as each Sabbath album that had less than 10 titles listed on the UK version contained 10 or more titles when released in the US.

For confirmation that these ‘extra’ titles were added after the albums were recorded, one only need to check out the handwritten track notes on the original tape boxes for the Sab’s first three albums (reproduced in Sanctuary’s 2009 CD reissues), indicating that these titles were not in use during the recording sessions. So: Extra song titles were added to each of Sabbath’s first five US releases to satisfy a stateside publishing deal. Mystery solved?! Probably.

Now that we have surmised the origin of these phantom titles, nagging questions remain: Were these titles just conjured out of nothing and slapped onto record labels for mere monetary gain? Or are they connected to any of the music on these records in some way? We can only guess… Um, hold on a minute… Besides also appearing on early cassette or 8-track tape runs, these song titles actually DID appear in one other notable place…

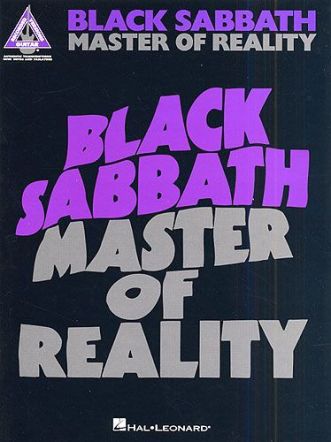

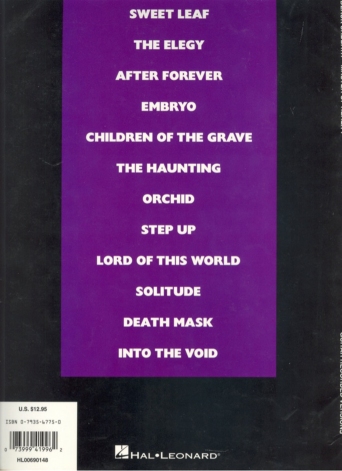

Hal Leonard Publishing, the music notation juggernaut, produced ‘easy guitar’ songbooks that were published concurrently with each of the Sab’s first five albums, and are still in print today. All of our phantom songs are included in these books, each of which provides ultimate confirmation of exactly where these musical mysteries reside. Where does ‘The Elegy’ end and ‘After Forever’ begin? Through the precise language of music notation, the Hal Leonard songbooks express these delineations explicitly, marking exactly where all of these ‘songs’ begin, end, and in some cases, reprise. While the titles and their sequencing on the early WB record labels provided clues, understanding exactly where these ‘songs’ reside is a futile exercise… Unless you can read music.

To save you the trouble of learning how to read music notation and/or spending fifteen bucks a pop on the HL songbooks, I’ve provided a rundown of Sabbath’s mystery songs, along with some pointers to understand exactly where and when they occur on each album. As you’ll see, some of these tags make perfect sense, while others seem quite random… the intro riff from ‘Lord of This World’ gets a title, but the intro riff from ‘Under the Sun’ doesn’t…? But again, the band only needed to choose two or three sections to name in order to reach that magic number of ten titles per record. Anyway, here we go:

I’ve already dissected ‘A Bit of Finger’, and ‘Bassically’ is pretty self-explanatory, but ‘The Wasp’ is a little tougher to nail down; Hal Leonard confirms that this piece of music acts as the intro to ‘Behind the Wall of Sleep’, it initially ends at the :32 mark and then kicks back in again at 2:30.

‘Luke’s Wall’ is the two-minute section that closes ‘War Pigs’. It starts at approx. 5:40 and ends the song by speeding up the tape to the point where this Black Sabbath masterpiece sounds like an Alvin and the Chipmunks song. Like, wow, man.

‘Jack the Stripper’ is the intro to ‘Paranoid’ album-closer ‘Fairies Wear Boots’. It wraps up it’s initial appearance at about 1:10, where the drum break carries us into the classic ‘Fairies’ riff; it reprises again at around 3:30 and repeats its lead-in to the main song.

‘The Elegy’ is the section of music that introduces ‘After Forever’, coming in immediately after that ominous phased tape loop that bookends the song. ‘Elegy’ reprises several times within ‘Forever’, and early Warner’s pressings listed this grouping as ‘AFTER FOREVER (Including ‘THE ELEGY’)’.

‘The Haunting’ is nothing more than the ghostly edge-of-feedback bent note that soars and dives throughout the slow fade at the close of ‘Children of the Grave’. Ozzy whispering the song title as the section fades was undoubtedly the inspiration for the iconic sounds that signal the arrival of Jason in the Friday the 13th movies. I can’t be the first one who’s noticed that…

‘Step Up’ is the riff that repeats for 30 seconds at the start of ‘Lord of This World’. It’s listed on the original solid green Warner Bros label as occurring before ‘Lord’ and its duration is time-stamped at :30, although it does appear again within the song, just after the chorus.

‘Death Mask’ is not only the greatest/heaviest muthafuckin’ riff of all time, but it’s also the intro to ‘Into the Void’. It’s likely that this was conceived as an song idea and given a title before it was attached to ‘Void’, as this segment was played live by itself as part of an extended jam inside an elongated ‘Wicked World’ in 1973 (See: ‘Live at Last’).

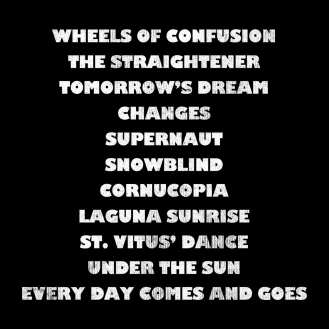

‘The Straightener’ is the instrumental section that quickly fades in and closes ‘Wheels of Confusion’ on the ‘Volume 4’ album.

‘Every Day Comes And Goes’ is the section in ‘Under the Sun’ where the song breaks down into a new riff, at double speed. The vocals start with the line ‘Everyday just comes and goes/Life is one long overdose’ etc, before moving into some jazzy soloing from Iommi and solo bits for Ward.

‘You Think That I’m Crazy’ is tacked onto ‘Killing yourself to Live’ and occurs between 2:45 – 4:08 (ish); while ‘I Don’t Know If I’m Up Or Down’ kicks off directly after that and winds up the song. These two pieces were likely written separately (and perhaps even assigned titles?) and connected during the songwriting process. The recognition of these two ‘ghosts titles’ imposes some structure on this somewhat-meandering piece of music and reveals ‘Killing Yourself to Live’ as a 3-part suite. Mind = Blown.

‘Prelude To A Project’ is the 45-second solo acoustic intro to ‘Spiral Architect’, the gorgeously epic finale to the ‘Sabbath Bloody Sabbath’ album. The ‘Crazy’, ‘Up or Down’, and ‘Prelude’ titles never made it onto any official release, not even on any of the record’s labels, and have only ever appeared in the official songbook from Hal Leonard in 1973.

So there you have it: we’ve cracked the Sabbath Code, solved a decades-old riddle and uncovered hidden dimensions in the understanding of Black Sabbath’s essential catalog. These troublesome titles have caused confusion and consternation among fans and collectors for decades– at least for those who were aware of their brief existence– but no more.

The inexplicable disappearance of these titles from subsequent US pressings, and the fact that these titles never appeared on any album covers (just on the labels) has made these ‘songs’ the stuff of legend and added to the dark mystique of early Black Sabbath. For you skeptics and/or agnostics who would prefer your Sabbath remain dark and mysterious, I will submit that I have not examined these titles for any secret messages, biblical codes or mathematical formulas… If anyone out there wants to take a crack at it, go for it. Let me know what you come up with. But please, be careful…

Legal Discliamer: This blog exists for infotainment purposes only. Consume at your own risk. In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from the summoning of demons, initiation of Armageddon, loss of soul, or insanity, arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this blog.

_________________________________

(This article copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Not to be republished without the express permission of the copyright holder.)

Special Thanks to my bud Monte Conner for instigating, inspiring, and informing this article with his November 25, 2018 Facebook post about this phenomenon, and to all who contributed to the thread. Oh, and to Hal Leonard!

Black Sabbath, with their dark lyrical imagery, menacing music, and apparent embrace of black magic, were the perfect band for the time, although this synergy wielded a double-edged sword: the band capitalized on the dark zeitgeist of the day, while the rock press blamed Black Sabbath for killing the hippie dream.

Black Sabbath, with their dark lyrical imagery, menacing music, and apparent embrace of black magic, were the perfect band for the time, although this synergy wielded a double-edged sword: the band capitalized on the dark zeitgeist of the day, while the rock press blamed Black Sabbath for killing the hippie dream. More Context: The high of choice at the dawn of the 1970s is actually a low. The use of psychedelics is on the wane; Downers are now the ‘in’ thing. Depressants like ‘reds’, Valium and Quaaludes, are where it’s at. I was amazed at the number of times Tuinal was mentioned in the many contemporary articles and reviews on Sabbath that I read to prep for this piece. Mike Saunders wrote in The Rag in 1971:

More Context: The high of choice at the dawn of the 1970s is actually a low. The use of psychedelics is on the wane; Downers are now the ‘in’ thing. Depressants like ‘reds’, Valium and Quaaludes, are where it’s at. I was amazed at the number of times Tuinal was mentioned in the many contemporary articles and reviews on Sabbath that I read to prep for this piece. Mike Saunders wrote in The Rag in 1971: Forty years ago, the young Sabs were not viewed by the press backward through the lens of four or five decades of rock and metal history, as they are today; rather they were a new band with a new sound, and could only be critically assessed against the bands of the day, particularly their ‘heavy’ contemporaries: Cream, Purple, Zeppelin, and Hendrix. When Sabbath first visited the U.S., they toured as an ill-fitting opening act for Cactus, Mountain, Canned Heat, Fleetwood Mac, Jehtro Tull, ELP, and Grand Funk Railroad, and later, headlining over Yes, Nazareth, Three Dog Night, Humble Pie, and Wild Turkey. Black Sabbath spawned a thousand imitators along the arc of their career, but in those early years, they were an anomaly; a band apart.

Forty years ago, the young Sabs were not viewed by the press backward through the lens of four or five decades of rock and metal history, as they are today; rather they were a new band with a new sound, and could only be critically assessed against the bands of the day, particularly their ‘heavy’ contemporaries: Cream, Purple, Zeppelin, and Hendrix. When Sabbath first visited the U.S., they toured as an ill-fitting opening act for Cactus, Mountain, Canned Heat, Fleetwood Mac, Jehtro Tull, ELP, and Grand Funk Railroad, and later, headlining over Yes, Nazareth, Three Dog Night, Humble Pie, and Wild Turkey. Black Sabbath spawned a thousand imitators along the arc of their career, but in those early years, they were an anomaly; a band apart. Touring the States repeatedly (eight times in 16 months) was part of it, but perhaps an even bigger factor was word-of-mouth. Sabbath was regarded as a ‘people’s band’, meaning ‘regular people’ dug them but the critics just didn’t get it (Grand Funk Railroad was perhaps the first band to be assigned this title; more on them in Part II). This ‘outsider’ status was pivotal to Black Sabbath’s early success… and every time a critic published a piece about how terrible Black Sabbath was, their legions of fans just loved and supported them even more. Black Sabbath did not just succeed despite the constant critical drubbing; in part, they thrived because of it.

Touring the States repeatedly (eight times in 16 months) was part of it, but perhaps an even bigger factor was word-of-mouth. Sabbath was regarded as a ‘people’s band’, meaning ‘regular people’ dug them but the critics just didn’t get it (Grand Funk Railroad was perhaps the first band to be assigned this title; more on them in Part II). This ‘outsider’ status was pivotal to Black Sabbath’s early success… and every time a critic published a piece about how terrible Black Sabbath was, their legions of fans just loved and supported them even more. Black Sabbath did not just succeed despite the constant critical drubbing; in part, they thrived because of it.